Doomscrolling seems to sum up last year for me. Festering in the onslaught of bleak news and hot takes on social media. Before this habit became septic, I used to experience a sort of perverse thrill in the expectation of dark announcements.

Segnius homines bona quam mala sentiunt, as the great Roman historian Livy put it, “men feel the good less intensely than the bad.”

Or in a more psychological analysis: negativity bias, the brain is more affected by unpleasant circumstances than positive ones. Experiencing a bigger jolt to the system in order to protect yourself from danger. Covertly anticipating the next dire headline so as to be overwhelmed with shock, anything to feel a bit more alive.

Yet my rush from negativity bias lies in its duality with positivity. 2020 was bombarded with bad news with very few moments of respite. So after many months of a downward spiral—COVID-19, dismal politics, police killings—the thrill has worn off.

Mark Fisher succinctly began his seminal 2013 essay Exiting the Vampire Castle with, “...incapable of productive activity, I found myself drifting through social networks feeling my depression and exhaustion increasing.”

Getting stuck in moralizing tweet threads and catastrophizing comments sections began to feel more and more corrosive. Sure, I’ve been able to read more books because of lockdowns and nightlife restrictions, but my time spent online also skyrocketed because of measures against the virus. My desire to stay the most informed on public health and culture wars led to information overload.

Amid the turmoil of 2020 I discovered a surprising digital antidote to doomscrolling and limited outings: looking at Catholic churches through livestreams.

What began as an art project in 2018 has ended up being a visual remedy for pandemic panic and internet antagonism, as well as an exploration into a digital service that has restorative qualities for my complex experience within a diaspora.

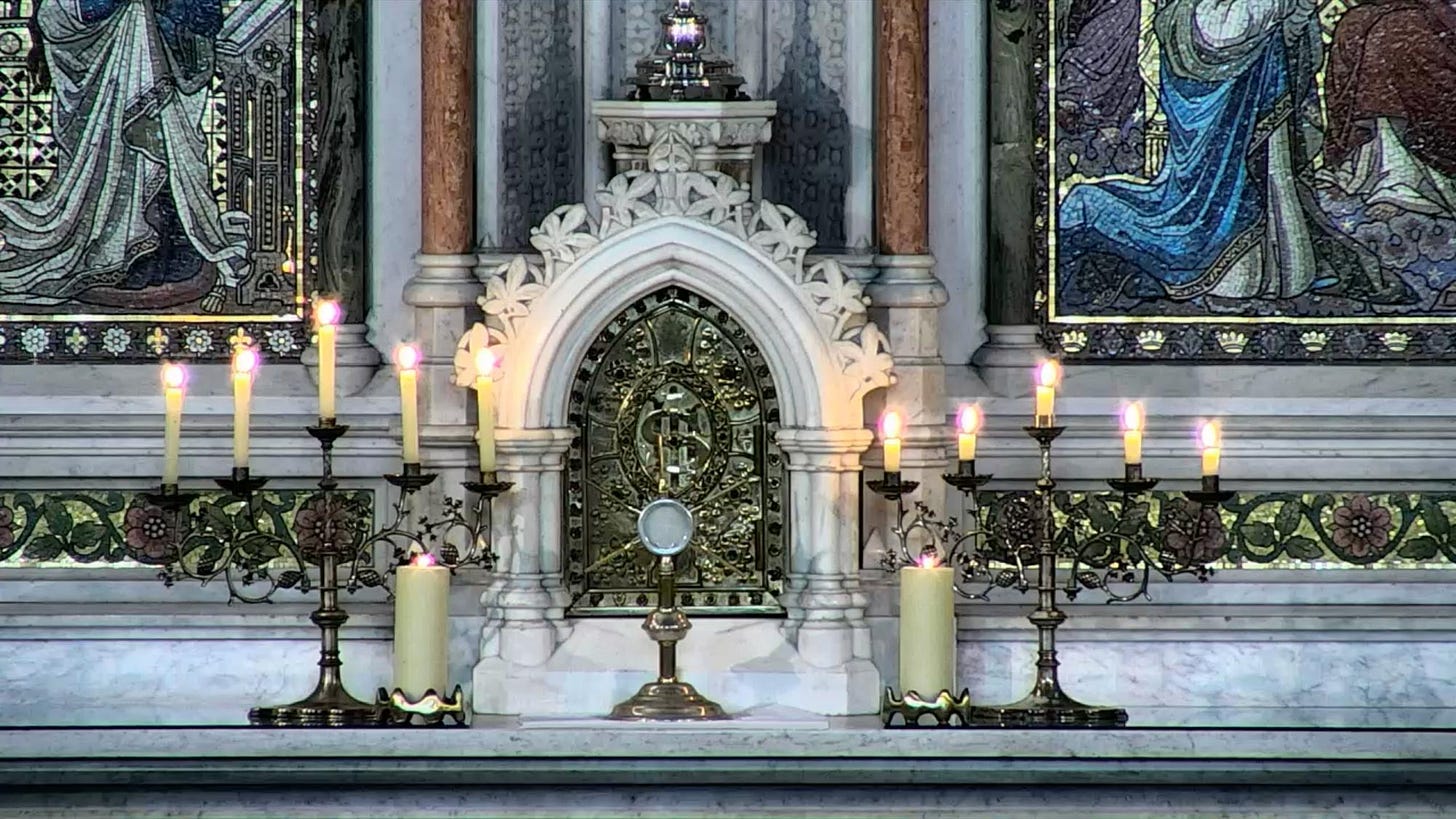

Whether you’re religious or not, it’s difficult to deny the beauty of most churches. Stained glass, lush marble, high ceilings, massive pipe organs. Their connection to antiquity and inherited pagan elements. Spaces that elicit such awe are far and few between nowadays.

Architecture from the last century has generally shifted focus to utilitarianism over aesthetics, a rejection of the decorative aspects of buildings. Living in areas fraught with eyesores, churches feel like remnants of a world prior to rapid urbanization. A time where ornate elements in public spaces were more valued.

ChurchServices.tv was developed in Ireland in 2005. The service enables parishes, mostly in Ireland, to livestream their masses. Their intention is to make mass as accessible as possible, like being able to spiritually tune in from your phone while commuting.

They also want to enable people to feel connected to their hometown parish despite geographical distance—resonating particularity with the Irish diaspora.

As a dual citizen of Ireland and the US (and living outside of both these countries for the last five years), these livestreams of Irish Catholic churches feel like an anchor of sorts in my transnational life. A mesmerizing ethnoreligious reminder of where I come from.

I was raised in a Catholic household on Long Island, New York by my Irish immigrant parents. We attended Sunday mass every week, and spent large chunks of our summers in Connacht visiting my grandmother and extensive extended family. In 2015, I moved from New York to Dublin.

I’ve been abroad ever since—between Berlin, Germany and Bristol, UK. Observing churches through livestreams has crystallized my understanding of their role in place attachment, providing me with a sense of rootedness while in my current hostland.

I began digitally hopping around churches in 2018 after reading an article by Daisy Jones about her perusing the platform Insecam. The website streams global public security cameras that aren’t password protected. Insecam has various filters, such as “river,” “mall,” and “laundry.”

Jones describes her voyeuristic exploration with an air of tranquility, experiencing “a sort of solitude, a specific type of observation, which isn't possible when you’re physically present within those environments.”

You can also filter by country on Insecam. Being a citizen of Ireland, I was curious to see what was there. It was mostly churches. My interest was piqued, especially as a lapsed Catholic. But further investigation of the Lord’s houses through Insecam felt incongruous.

The website’s basis seemed slightly off-kilter for liturgical excursions—their primary intention is to highlight the lack of security in video surveillance. I sought a more pertinent alternative, leading to my discovery of ChurchServices.tv and more recently Churchtv.ie, also developed in Ireland.

Viewing Irish churches through livestreams has given me a way to observe Catholic institutions in real time across the country that shaped my parents’ beliefs, the same beliefs that shaped me as a child.

Taking cues from Mark Power’s study of Polish churches (in Mass) through a lapsed Catholic eye, I’ve had a cathartic reexamination of a religion that was once so integral in my life. And as a visual artist who’s invested in looking and creating sumptuous images, these livestreams became my muse.

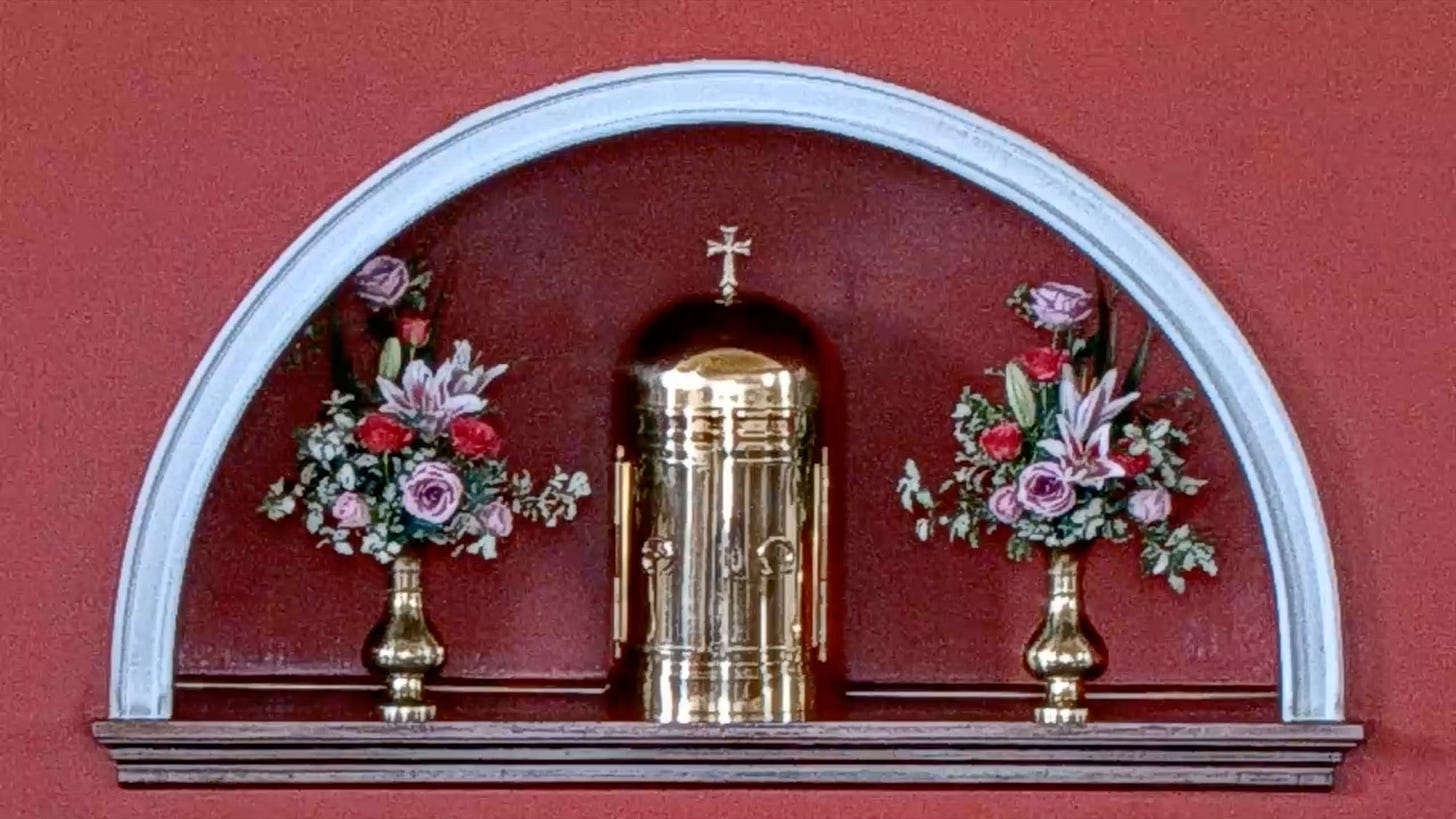

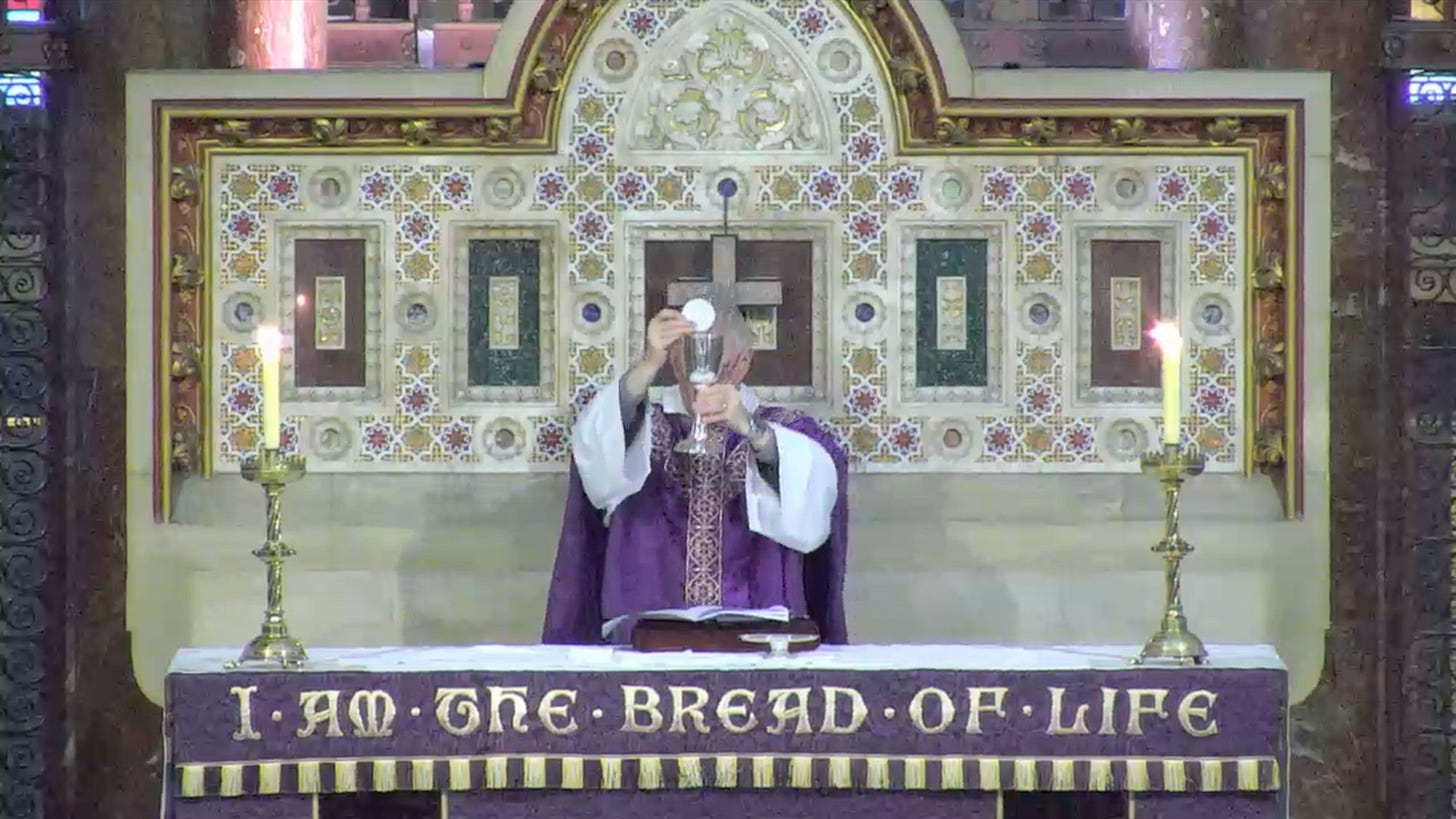

Ritual, sacraments, clerical clothing, and doxology engrossed me. Like Dorian Gray’s fascination with ecclesiastical performance and accoutrements, I too have become captivated by the glamor of the vestments and liturgical objects. The minutiae of creed hasn’t interested me, but the otherwordly ambiance has, even through my 16-inch Macbook screen.

My newfound interest and art could be adjacent to the current Weird Christianity wave, as Tara Isabella Burton describes as, “equal parts traditionalism and, well, punk: Christianity as transgressive alternative to contemporary secular capitalist culture. Like punk, Weird Christianity has its own, clearly defined aesthetic.”

Rather than online stress-purchasing frivolous items, I can admire dazzling chasubles in action. Only now am I coming to appreciate the pomp of my formative environment.

The state of watchfulness triggered by these livestreams is similar to viewing slow television. Slow tv was pioneered by Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) in 2009 with their filming of the seven hour train route from Bergen to Oslo. NRK’s trailblazing with slow tv was a huge hit for Norwegians, as residents felt invested in the journey.

Anticipating to see an area special to them, leisurely reflecting on their past memories of such locations. Available through public broadcasting, culturally conscious filming provides the masses relief from chaotic fast cutting film editing that is so rampant in modern visual culture.

Livestreaming Catholic churches in Ireland feels related to this Norwegian cultural ode. Tapping into the collective Irish memory, honoring staples of the homeland through straightforward and thoughtful filming.

Of course this can’t be mentioned without acknowledging the transgressions of the Catholic church—bad actors have certainly tainted these spaces for many. Irish conservatism stemmed from parochial influence has caused detrimental affairs, like the Magdalene Laundries.

Extremes aside, watching these livestreams provides me with a certain type of pacification while evoking nostalgia. Beyond the initial allure of the ritz, these are digital spaces for contemplation, specific to my immigrant status. People in diasporas particularly derive value from technology.

The bilingual Berlin subreddit guides me on the sanest path towards securing my Anmeldung (registering where I live), by giving me the nitty-gritty legal details in plain English. My dad streams Connacht radio stations through an iOS app while woodworking in Queens. Fringe memes are sent by my cousins across oceans in our Whatsapp group.

There’s an ability to remain connected to facets of cultural roots and places once called home—there’s solace in that, especially in moments when I feel out of place while living abroad.

As I’m in flux between countries, I’m soothed by the brogues of the clergy stemming out of my computer speakers. The familiar accent that sang throughout my childhood home, the one that my American friends often couldn’t understand.

When bells are rung, I’m reminded of the Angelus emitting through my grandmother’s television at noon and dusk, in her cozy home amid the most bucolic setting.

During transubstantiation, I think of eating fresh bagels with my brother after communion. I likely physically attended upwards of one thousand masses before the age of eighteen.

It’s a relief to have access to new digital content that feels so pure—no communication software features that contribute to engagement data, no intrusive ads. Just an abundance of streams featuring stellar settings and mystical rituals led mostly by ascetic elders.

COVID-19 brought upon a lot of uncertainty and isolation. Further prompting the popularity in livestreaming mass, as physical attendance became restricted. With life being so online as of late, this practice has granted me moments to tune out the barrage of media sensationalism.

Capturing visually striking moments has been creatively satisfying while comforting. It goes without saying that the religion clearly has a keen sense of aesthetics.

Catholic iconography has been lauded and appropriated in pop culture for decades. From Madonna and Billy Idol’s sporting of the crucifix, to the Met Gala’s 2018 theme Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination.

Nicholas Mirzeoff questions accessing the sublime through the computer in An Introduction to Visual Culture:

"The pixelated image is perhaps too contested and contradictory a medium to be sublime...even the most sophisticated screen has a certain emptiness to it...unlike photography and film which attested to the necessary presence of some exterior reality, the pixelated image reminds us of its necessary artificiality and absence. It is here and not here at once.”

The sublime elicits awe and fear. Churches satisfy my desire for beauty and shock. They remind me of my finitude, the passage of time, the practices of those long before me, and those who will come after me.

Contemplating Catholic decor and the Eucharist takes me to a place beyond the mundane—stuck more than ever in my apartment, with my outings to the grocery store as some of my main weekly highlights. Indeed, a livestream is by no means an adequate alternative to the august ambiance that comes with being physically inside a church.

Yet in the shackles of internet dependence and pandemic-induced cabin fever, I believe that these virtual transportations to sanctified places—so emblematic of my youth and heritage—are the closest digital versions of the sublime.

In Culture of Narcissism Christopher Lasch states, “people demand from personal relations the richness and intensity of a religious experience.” His observation has stuck with me. With the restriction of socializing, I’ve realized how it’s important to be able to access profound moments on my own terms.

Although I’m not necessarily seeking to attain ecstasy through creed, the aura and splendor of these religious buildings and ceremonies can be a means of feeling the extraordinary in an ordinary world.

Capturing these settings and scenes has also provided me with a different mode of creating work, one that’s a bit more inward and transcendent.

These images are intergenerational compositions. Representing my appreciation for internet art as a millennial and my reverence for ancestral tradition. Utilizing twenty first century technology within twentieth century (and beyond) buildings.

Akin to Jon Rafman’s Nine Eyes of Google Street View—featuring peculiar scenes captured by Google Street view—using digital tools can lead to serendipitous art. In the drudgery of techno-pessimism, there can be oases.

My images are not only a pleasing look into landmarks from one of my home countries, but also an appreciation for tranquility. And the ability of public spaces, art, and technology to foster that.

Stay tuned for my upcoming monograph Finding the Sublime Online—where photographs from this series expand into the UK.